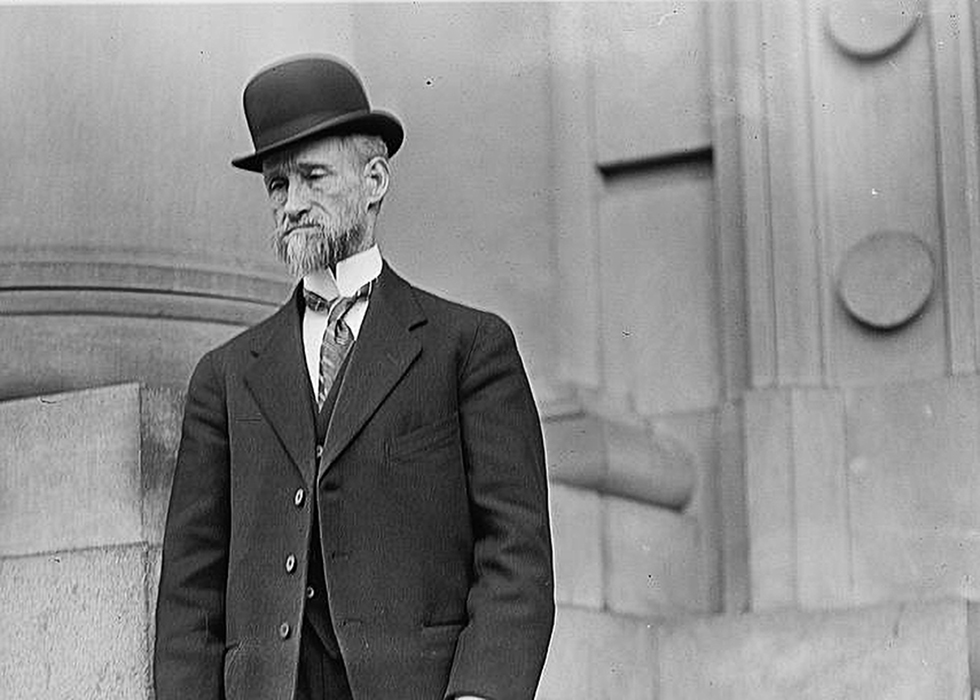

Governors of Georgia: Joseph M. Brown

Oakland Cemetery is home to many important mayors, celebrities, and public officials. Among these individuals are six governors who today reside inside its hallowed grounds. This blog series will explore these six men: their successes, their failures, and their impact on the people of Georgia.

Joseph M. Brown was the third child of Joseph E. Brown, the wartime governor of Georgia and an Oakland resident. “Little Joe Brown,” a family nickname, studied law but was not able to make it a career. His diligent studying caused his eyesight to fail, making it impossible to work as a lawyer. Brown decided to work for the railroad instead. In 1877, he was hired by the Western & Atlantic Railroad, a state-owned route leased to a company led by the elder Joseph Brown. The younger Brown began as a conductor and eventually became a traffic manager. As part of his work with the Western & Atlantic, Brown authored a book on the Atlanta Campaign of the Civil War titled Mountain Campaigns in Georgia. Another early accomplishment was helping to create orange and watermelon industries in Georgia. Under his direction, Western & Atlantic representatives traveled around South Georgia to encourage the growth of these plants.

In 1904, Brown joined the Georgia State Railroad Commission. During the 1906 gubernatorial election, former Secretary of the Interior Hoke Smith declared that he would try to control the power of the railroads. The inaugural speech for his campaign was titled “No Quarter for Railroads.” Smith wanted Americans, not “foreign corporations or non-resident citizens,” to own Georgia’s railroads. Smith also advocated for expanding the Georgia State Railroad Commission’s membership from three to five. Joseph M. Brown vehemently opposed these policies. Smith won the 1906 election and dismissed Brown from the Georgia State Railroad Commission in August 1907. Brown’s replacement was dismissed around a year later for similar reasons.

At the same time as his dismissal, Brown published his only novel, Astyanax. In the stories of the Trojan War, Astyanax is the young son of the Trojan hero Hector. Astyanax always dies, with the only variation being how gruesome the death. In Brown’s story, Astyanax survives and leads the Trojans aboard the ship Atlanta to “Amaraca,” a fictional ancient name of North and South America. They attempt to create a new Ilion, or Troy, in Amaraca. The story is a romance between Astyanax and Princess Columbia. Atlantis also plays a key role.

According to William J. Northen, a historian, former Governor of Georgia, and Oakland resident:

Impressed by the descriptions of the massive ruins of ancient edifices throughout the three Americas, it occurred to Governor Brown that a fascinating story might be builded [sic] which, utilizing the relics of antiquity, along with the heroic characteristics of the natives as discovered and warred with by the early settlers from Europe, would satisfy the tastes and gratify the pride of the peoples of the American hemispheres and teach American youth that on our side of the Atlantic lived exemplars as noble as the Gracchi [The Gracchi brothers lived in Republican Rome and tried to reform its institutions], and conquerors who founded empires greater in area than did Alexander or Caesar.

The complete Astyanax can be found for free online here.

Hoke Smith became a political enemy after he dismissed Brown from the Georgia State Railroad Commission. Brown decided to challenge Smith for governor in 1908. After a bitter campaign, Brown emerged as the victor. Their bitter fighting played out in newspapers; Brown never gave a single campaign speech in 1908. This term in office is remembered for Brown’s enforcement of a statewide alcohol prohibition and the state’s first automobile registration laws.

Brown and Smith had a rematch in the 1910 election. Brown again declined to make speeches, but unlike two years before, Smith emerged victorious. After Smith resigned in 1911 to serve in the U.S. Senate, Brown was elected to serve the remainder of the term. Learning from his mistake in 1910, he did give a campaign speech, although it was only ten minutes long. During his second term, it was remarked that he was in “personal and political favor with a majority of the people of the Commonwealth.” Historian James F. Cook noted that in his second term, Brown “rarely offered workable solutions to the problems he attacked.” In fairness, his term was only around a year long. Cook also noted that his time in office was “a respite from the hectic pace of change” that marked the governorship of Hoke Smith.

After leaving office in 1913, Brown lived in Cobb County and Cherokee County. During and after the Leo Frank trial in 1913, Brown and Tom Watson vocally advocated for Frank’s execution. They urged the “law be allowed to take its course” even if the law was wrong. Both men made antisemitic comments about Frank, which helped to turn the public against Leo Frank. Today, the consensus is that Frank was wrongly convicted.

After Governor John M. Slaton commuted Frank’s death sentence to life imprisonment, many believe Brown organized Frank’s lynching by a violent mob. Frank was taken from the prison in Milledgeville by twenty-five men, brought to Marietta, and hanged from a tree. Frank’s body became an attraction. Thousands of spectators later visited the mutilated corpse at the morgue.

Towards the end of his life, Joseph M. Brown struggled with health problems. When he passed away in 1932, he was buried near his father in Oakland Cemetery. Brown is best remembered for his connections to the Leo Frank case. His governorship saw no major reforms during an era in our state’s history hallmarked by rapid change.

Click for Sources

SourcesBrown, Joseph M. 1907. Astyanax; an Epic Romance of Ilion, Atlantis & Amaraca. Hathi Trust Digital Library. Broadway Publishing Company. https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/000281778.

Cook, James F. 2005. The Governors of Georgia: 1754 – 2004. Third Edition, Revised and Expanded. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press.

MacLean, Nancy. 1991. “The Leo Frank Case Reconsidered: Gender and Sexual Politics in the Making of Reactionary Populism.” The Journal of American History 78, no. 3: 917–48. https://doi.org/10.2307/2078796.

Moseley, Clement Charlton. 1967. “The Case of Leo M. Frank, 1913-1915.” The Georgia Historical Quarterly 51, no. 1: 42–62. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40578874.

Northen, William J., ed. 1908. Men of Mark in Georgia. Vol. 7. 7 vols. Atlanta, GA: A. B. Caldwell.

Wheeler, Kenneth H., and Jennifer Lee Cowart. 2003. “Who Was the Real Gus Coggins?: Social Struggle and Criminal Mystery in Cherokee County, 1912–1927.” The Georgia Historical Quarterly 97, no. 4: 411–46. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24636328.