Governors of Georgia: John M. Slaton

Oakland Cemetery is home to many important mayors, celebrities, and public officials. Among these individuals are six governors who today reside inside its hallowed grounds. This blog series will explore these six men: their successes, their failures, and their impact on the people of Georgia.

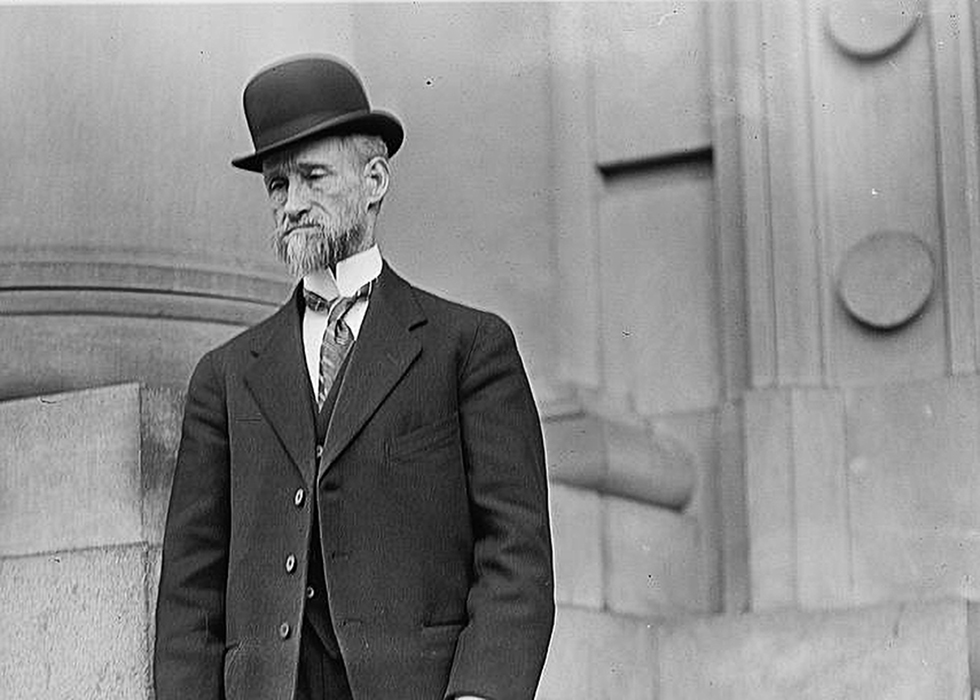

John Marshall Slaton was born on Christmas Day, 1866. He spent most of his childhood in Meriwether County but graduated from high school in Atlanta. Slaton attended the University of Georgia, became a lawyer, and settled in Atlanta. In 1896, he was elected to the Georgia House of Representatives. He would stay in the House until 1908. From 1909 to 1913, Slaton served in the Georgia Senate. When Hoke Smith resigned as governor in late 1911, Slaton was the President of the Senate. In that role, Slaton became the acting governor and held the position for two months. In 1912, he ran for Governor of Georgia and got three-fourths of the popular vote. Slaton proved to be a popular governor. He advocated for tax reform, utility legislation, and leasing the Western & Atlantic Railroad. His popularity ended abruptly when he had only one week left in office.

One of the darkest chapters of Atlanta’s history is the trial of Leo Frank. Frank was the Jewish superintendent of the National Pencil Factory in Atlanta. On April 26, 1913, the body of murdered employee Mary Phagan was found inside the factory. Three arrests were made: guard Newt Lee, Leo Frank (as a witness, not a suspect), and Jim Conley, an African-American floor sweeper. Lee and Conley were set free. Despite a lack of evidence, Frank became a suspect. Public opinion quickly turned on Frank, and antisemitism was rampant. Jim Conley became the star witness against Frank. Conley’s evidence implicated himself; he is now believed to have been the killer.

Frank was found guilty of murder based on evidence that was flimsy at best, and he was sentenced to hang.

Despite the prevalence of antisemitic public opinion, many Georgians pressured Governor Slaton to commute Frank’s sentence. He received “thousands of letters” to that effect. The Atlanta Journal also advocated for commuting his sentence. According to Slaton, Georgia political leader Tom Watson told him that if Slaton would “let the Jew hang, he would elect [Slaton] as United States Senator from Georgia, and make him master in National Politics in Georgia for ‘twenty years to come’.”

Leo Frank’s execution was set for June 22, 1915. The day before the scheduled tragedy, Governor Slaton commuted the sentence of Leo Frank to life in prison. This single act entirely ended the political career of John M. Slaton. An antisemitic mob marched on Atlanta, crying that they wanted “John M. Slaton, King of the Jews and traitor Governor of Georgia.” (“King of the Jews” was an odd choice of phrase, as it is used prominently in the Bible to describe Jesus.) Tom Watson compared Slaton to Benedict Arnold.

Slaton’s term ended exactly one week later. After leaving office, he went on a trip across the country. On August 16, 1915, a lynch mob took Frank from a Milledgeville jail and transported him to Marietta to be murdered. One of the mob’s leaders was former Governor Joseph M. Brown. No members of the mob were punished. Frank was posthumously pardoned in 1986.

After the abrupt end of his political career, Slaton joined an unexpected venture with Henry Ford. In the initial stages of World War I, Ford felt that peaceful mediation could end the conflict. He hired a boat, dubbed the Peace Ship, and set sail in late 1915. Ford invited prominent politicians, faith leaders, and educators to participate. Slaton accepted the invitation. The press widely ridiculed the event, and many delegates disagreed about their strategy once they reached Europe. Needless to say, Ford was unsuccessful in stopping the war. (Ironically, Ford has also been credited with stoking antisemitic feelings in America.)

During World War I, Slaton lived in Romania and worked for the Red Cross. After the war’s end, he returned to Atlanta to resume his law career. He unsuccessfully ran for the U.S. Senate in 1930, his only major election after 1915. Slaton never held a political office again though he was elected president of the Georgia Bar Association in 1928. Between 1954 and 1955, Slaton wrote the “Slaton Memorandum,” a document explaining why he commuted Frank’s sentence. The Slaton Memorandum was not published until 2000. Slaton noted in the document’s introduction that he had been asked by “many persons to write out [the] facts influencing” him in the Leo Frank case. In the final paragraph, Slaton noted:

I did what my sense of justice and my conscience demanded that I do. The effect of my action upon my political future was not a matter to which I paid any attention, and I did my duty under the facts as presented to me, and that was all that was required of me. I practiced law in Atlanta with a clear conscience, and I would not have changed my action. The case was finished as to me, when I signed the order granting the commutation.

John M. Slaton passed away in 1955 and was buried in Oakland Cemetery. John Marshall Slaton, “the traitor Governor of Georgia” from the “same mold as Benedict Arnold,” is now well remembered for his noble stand against mob rule.

Seventeen-year-old Andrew Bramlett is a local historian living in Kennesaw, Georgia. Named the 2023 Honorary City Historian for the City of Kennesaw, he is vice president of the Kennesaw Historical Society, an Honorary Member of the Cemetery Preservation Commission for the City of Kennesaw, and the archivist for the Save Acworth History Foundation. He volunteers with the Kennesaw Parks & Recreation Dept. and volunteers at Kennesaw Mountain National Battlefield Park, where he is a tour guide on the shuttle bus to the top on the weekends. Andrew speaks to civic groups, senior centers, and community groups on a variety of topics ranging from local history to topics that can be used anywhere in the world.

Click for Sources

SourcesCook, James F. 2005. The Governors of Georgia: 1754 – 2004: Third Edition, Revised and Expanded. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press.

Goldfarb, Stephen J. 2000. “The Slaton Memorandum: A Governor Looks Back at His Decision to Commute the Death Sentence of Leo Frank.” American Jewish History 88, no. 3: 325–39. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23886389.

Greene, Melissa Fay. 1998. “The Old History-as-Novel Gambit: Leo Frank as a Fictional Character.” The Georgia Historical Quarterly 82, no. 1: 73–83. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40583697.

Guinn, Jeff. 2019. The Vagabonds: The Story of Henry Ford and Thomas Edison’s Ten-Year Road Trip. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster Paperbacks.

“John Marshall Slaton.” National Governors Association. Accessed January 13, 2022. https://www.nga.org/governor/john-marshall-slaton/.

MacLean, Nancy. 1991. “The Leo Frank Case Reconsidered: Gender and Sexual Politics in the Making of Reactionary Populism.” The Journal of American History 78, no. 3: 917–48. https://doi.org/10.2307/2078796.

Moseley, Clement Charlton. 1967. “The Case of Leo M. Frank, 1913-1915.” The Georgia Historical Quarterly 51, no. 1: 42–62. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40578874