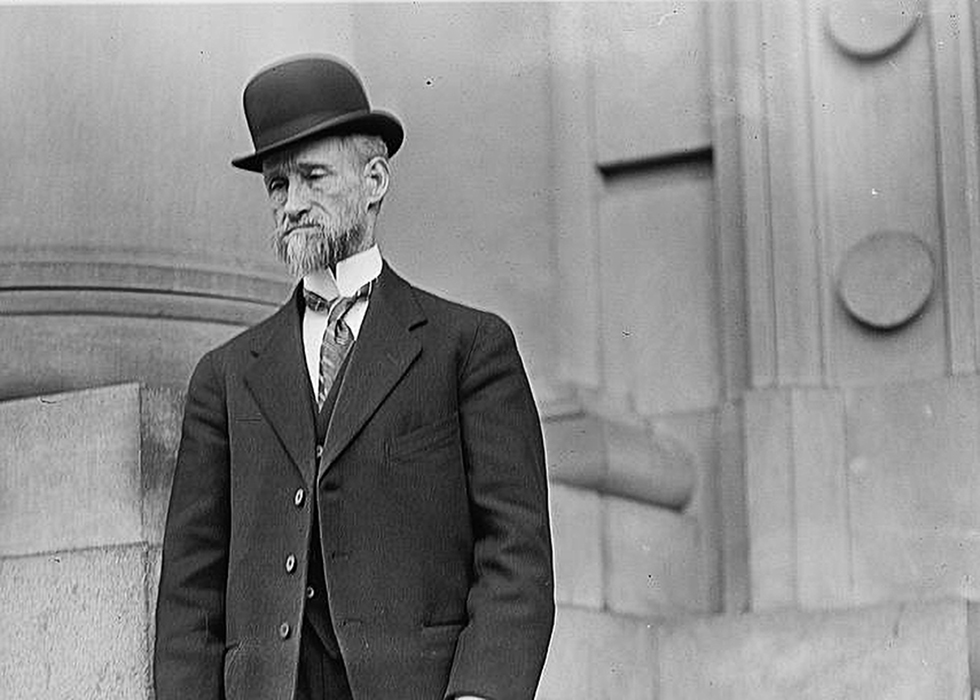

Governors of Oakland: William J. Northen

Oakland Cemetery is home to many important mayors, celebrities, and public officials. Among these individuals are six governors who today reside inside its hallowed grounds. This blog series will explore these six men: their successes, their failures, and their impact on the people of Georgia.

Born in 1835, William J. Northen grew up in Jones County on his father’s plantation. He graduated from Mercer University in Macon and joined Mt. Zion Academy in Hancock County as an instructor. Northen later became assistant principal and later headmaster. At the start of the Civil War, Northen enlisted in the Confederate Army as a private. But he only served in combat until 1862. He worked in Confederate hospitals for the remainder of the war.

After the war, Northen returned to teaching but his health forced him to retire in 1874. He decided to become a farmer. Northen conducted experiments to improve his crop yield and the quality of his cows’ milk. He was willing to share these innovations with his friends. Northen helped establish the Hancock County Farmer’s Club, a group that provided ideas and support to local farmers. Northen gained name recognition for his work as an agricultural reformer.

After the war, Northen returned to teaching but his health forced him to retire in 1874. He decided to become a farmer. Northen conducted experiments to improve his crop yield and the quality of his cows’ milk. He was willing to share these innovations with his friends. Northen helped establish the Hancock County Farmer’s Club, a group that provided ideas and support to local farmers. Northen gained name recognition for his work as an agricultural reformer.

Using this fame, Northen ran for office in the Georgia House of Representatives in 1877. He served one term and returned for a second term two years later. At the end of that term, Northen was elected to the Georgia Senate. In his first term, he presented a bill allowing county citizens to vote on whether or not they would allow alcohol in their area. Called the Local Option Law, it was supported by a state temperance convention. On July 14, 1881, Northen presented the bill. He brought with him (in the style of Mr. Smith Goes to Washington) the full petition with six-hundred feet of signatures. “Mr. Northen goes to Atlanta” was less successful. Northen tried to revive the bill in 1884 and saw similar results. The Local Option bill finally passed in 1885 and directly contributed to prohibition in Georgia.

In 1886, Northen was elected president of the Georgia State Agricultural Society. In 1890, he decided to run for Governor of Georgia as a Democrat. The Georgia Democratic Party was split into two factions, the Bourbons and the Farmers Alliance. The Bourbons were advocates of the “New South” and a move towards an industrialized economy. The Farmers Alliance, named after a powerful agricultural organization, was a more conservative side of the party. The Bourbon’s power in Georgia was waning, and Northen’s primary opponent was a member of the Farmers Alliance faction named Leonidas Livingston. Livingston, like Northen, had previously served as head of the Georgia State Agricultural Society. The Farmers Alliance faction was split in its allegiance, but Livingston left the race to run for a congressional seat. This move left the field open for Northen’s nomination.

The Populist Party, led by Tom Watson, gained power in Georgia in the late nineteenth century. Despite the Populist rise in power, Northen easily defeated Populist candidate W. L. Peek in the general election. The Populist Party would remain a thorn in Northen’s side for the rest of his time in office. During his two terms as governor, Northen was known as a conservative. He was a resolute supporter of farmers and, given his earlier career as a teacher, schools.

Governor Northen undertook an unprecedented campaign to combat racial violence. The rise of lynching murders of African Americans deeply concerned him. He traveled across the state to endorse racial cooperation and antilynching measures. In an 1892 speech before the General Assembly, Northen claimed:

“These self-constituted judges and executioners are more than murderers. They have not only taken human life without authority or excuse, but they have put before their fellow-citizens an example which, if followed to any extent, would speedily result in the dissolution of society itself.”

In response to this speech, a law was created to put an end to mob violence in Georgia. The law required sheriffs to gather men to stop lynching murders. Sheriffs who failed to comply could be tried for murder. The law saw initial success, but loopholes were later exploited and efforts to amend the law failed. It is also known that Georgians who disliked Northen’s lynching policies sent him photographs of their crimes. Worse, some murderers sent him parts of their victims.

Despite his hatred of racial violence, Northen was still very prejudiced. He believed the race relations in the South should be solved by whites only. In an 1899 speech given in Boston, he expressed disappointment that noted African American journalist Ida B. Wells could “electrify two continents with incendiary statements made from the lecture platform… grossly misrepresenting the South.” Northen contrasted this to Dr. Nehemiah Adams and Amelia Murray, who had both written books before the Civil War in favor of slavery. Northen himself condemned slavery but felt the two were unjustly attacked. Northen asked if “the day will ever come when the South can be heard without prejudice and her people accorded a fair audience before the world?” In the same speech, he expressed fears of interracial marriage before finishing with a history of slavery in the United States favorable to the South.

While holding the office of Governor, Northen got involved with the Georgia Baptist Convention and the Southern Baptist Convention. After he left office in 1894, Northen served as president for both groups. From 1907 to 1912, he compiled a series of books called Men of Mark in Georgia. Northen’s biography, written by his publisher A. B. Caldwell, is found in Volume IV. Northen must have enjoyed reading descriptions of himself as “a consecrated public servant,” “a conscientious and wise legislator,” “a practical, progressive farmer,” “a devoted teacher,” and “an honored and beloved private citizen.”

William J. Northen was buried at Oakland Cemetery when he passed away in 1913. He has been remembered as an “honest and competent” governor and as a religious leader in our state. His efforts in passing anti-lynching laws show a dedication to protecting all Georgians, even though he shared the prejudices of many of his contemporaries.

Andrew J. Bramlett is a 15-year-old historian living in Kennesaw, the site of the start of the Great Locomotive Chase. He was elected vice president of the Kennesaw Historical Society in 2015. He volunteers at Kennesaw Mountain National Battlefield Park, the Kennesaw Cemetery Preservation Commission, the Kennesaw Parks and Recreation Department, and the Friends of Kennesaw Mountain. In 2018, he won a Georgia Historical Records Advisory Council award for Local History Advocacy because of his work on presentations he gives about the history of the City of Kennesaw, Kennesaw Mountain, and his Kennesaw City Cemetery Walking Tour.

Andrew gives presentations, speaking to civic groups, senior centers, and community groups on a variety of topics ranging from local history to topics that can be used anywhere in the world. More info can be found on his website, ajbramlett.com.