Resident Spotlight: Charles J. Haden’s Brush with Presidential History

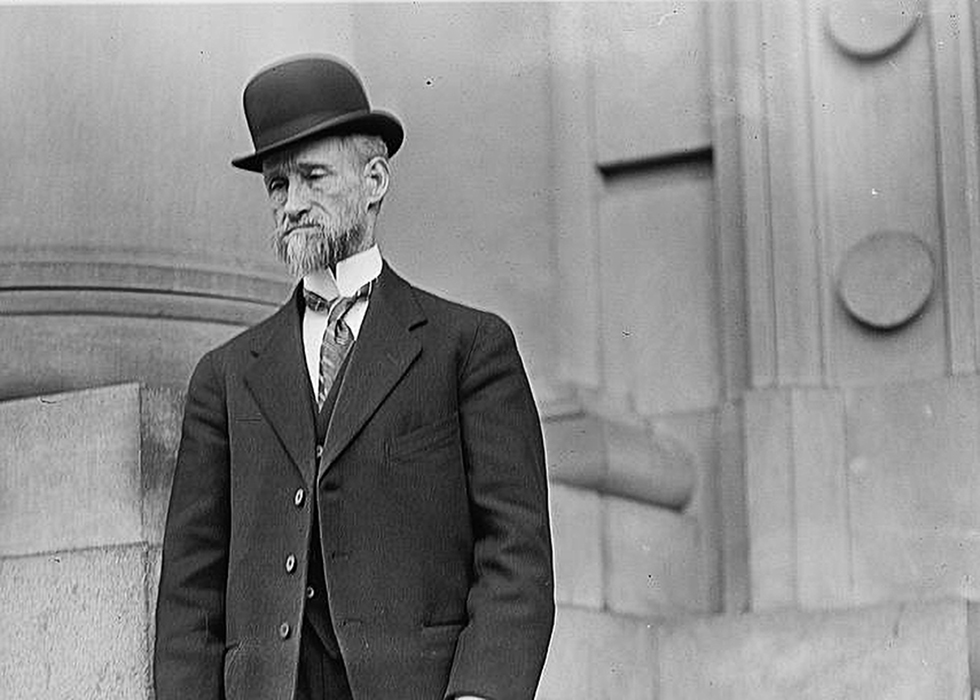

It was November 1919, and future Oakland resident Charles J. Haden was presumably honored to be one of many prominent Atlantans about to hear the vice president speak. The venue was the Atlanta Auditorium, one of the city’s most impressive spaces with its arena seating and massive pipe organ. The vice president spoke of patriotism, duty, and honor to the Loyal Order of Moose. Suddenly, coming from the side of the hall was the story that would make this speech a footnote in American history. A man rushed up to Haden and asked him to pass along a message to the vice president: The president had just died in Washington. In that instant, Haden became one of the first Americans to hear that Thomas Marshall had become the twentieth president.

Of course, there never was a President Thomas Marshall who filled in after the death of President Wilson. Wilson, though his health was faltering, was undoubtedly not deceased. Yet the above incident did occur, and Haden did tell Marshall, and Marshall, for the briefest of time, thought he was really the president. This somewhat ridiculous tale perhaps gives Haden a more unusual presidential connection than any other Oakland resident.

The central Atlantan in this saga is Charles J. Haden, who was born in Huntsville, Alabama on March 17, 1863. Early in his career, he worked for Alabama newspapers before moving to Atlanta in 1881. Haden eventually became a lawyer, and according to his obituary in the May 23, 1948 issue of the Atlanta Journal “handled all the details” when G. V. Gress gave the Cyclorama to the City of Atlanta. Haden was an avid researcher of Southern history, and in particular, helped memorialize songwriter Stephen Foster and politician William H. Crawford. At the time of World War I, he was living on Peachtree Street near today’s High Museum. His law office was in the W. D. Grant Building downtown.

After returning from negotiating the Treaty of Versailles, President Woodrow Wilson faced the uphill task of convincing Congress to approve the treaty. His primary opponent was Henry Cabot Lodge, who opposed the treaty’s provision about a League of Nations. To drum up support for the treaty, Wilson traveled by train across the United States to appeal to the American public directly. He collapsed from exhaustion while in Colorado, and after returning to Washington in early October, he suffered a stroke. Willson never fully recovered. For the remaining year and a half of his presidency, he was incapacitated and closely guarded by his wife, Edith. The vice president, Indiana native Thomas R. Marshall, was told of the situation but did not take on the powers of the president.

Marshall, in his memoirs, said there was a “standing joke of the country… that the only business of the vice-president is to ring the White House bell every morning and ask what is the state of health of the president… I was not that soul.” He had no love of the office of vice president, once comparing it to “a monkey cage, except the visitors do not offer me peanuts.” Many had presidential hopes for the respected Hoosier, and Marshall expressed interest in running in 1920. In November 1919, he traveled around the country to inspire the people to vote Democrat in the next year’s elections. He visited Columbus on November 22 and spoke at Atlanta to the Loyal Order of the Moose the next day.

Tell him it’s the Associated Press and that President Wilson’s dead, and he’ll come to the phone.

During Marshall’s speech at the Atlanta Auditorium, one of the building’s custodians, G. T. Christian, answered a telephone call from a man asking to speak to Marshall. Christian said Marshall was unavailable, so the voice on the other end said, “Tell him it’s the Associated Press and that President Wilson’s dead, and he’ll come to the phone” and hung up. Startled, Christian found a police officer, and together, they went near the stage to alert someone. They found Haden (it is unclear why they chose him for the task) and asked him to relay the vital information.

Haden stepped next to Marshall and whispered in his ear before announcing to the crowd the terrible turn of events. Everyone was stunned. The supposed new president addressed the crowd by saying, “My friends, if this sad news is true, I can not take up the burdens of our great chieftain unless every patriot in the country will help and pray for me!”

The organist began to play “Nearer my God to Thee.” As soon as he could, Marshall found a telephone and called Washington. The White House confirmed that Wilson was still alive, and Marshall was relieved. During these few minutes, he had felt the burden of the presidency on his shoulders and decided against running in 1920. Discovering that the phone call had been a prank did not change his opinion. Marshall revealed his opinion to the New York Times in December 1919. After the end of his term, he retired to Indiana, wrote his memoirs, and settled down before passing away in 1925. It is said that when Calvin Coolidge was elected vice president in 1920, Marshall sent his condolences.

The authorities in Atlanta never found who made the prank phone call, even after Governor Dorsey offered a reward ($100) for anyone with information. After about a week, it faded from memory, though it was mentioned in the only two biographies of Thomas Marshall to ever be published.

After his close encounter with history, Charles Haden stayed in the Atlanta area. His obituary in the Atlanta Journal noted that he was concerned with “the problems confronting the Southern farmer… and he took a stand favoring the removal of restrictions on oleomargarine” in the 1930s. He also was a leader of soil conservation efforts. Haden also became active with the Masons and was president of the Georgia Chamber of Commerce. At the time of his death, he was living on Peachtree Street opposite Rhodes Hall. He passed away on Mary 23, 1948, and was laid to rest at Oakland. The Atlanta Constitution noted that he “combined the best traditions of the Old South with the enterprise of the new.” None of his obituaries mentioned the incident at the Atlanta Auditorium in 1919.

Seventeen-year-old Andrew Bramlett is a local historian living in Kennesaw, Georgia. Named the 2023 Honorary City Historian for the City of Kennesaw, he is vice president of the Kennesaw Historical Society, an Honorary Member of the Cemetery Preservation Commission for the City of Kennesaw, and the archivist for the Save Acworth History Foundation. He volunteers with the Kennesaw Parks & Recreation Dept. and volunteers at Kennesaw Mountain National Battlefield Park, where he is a tour guide on the shuttle bus to the top on the weekends. Andrew speaks to civic groups, senior centers, and community groups on a variety of topics ranging from local history to topics that can be used anywhere in the world.

Sources

Atlanta City Directory Company’s Atlanta City Directory – 1919 – Containing an Alphabetical List of Business Firms, Corporations Followed by Their Officers, Copartnerships Giving Names of Partners, and Private Citizens with Their Occupation, Business Connections and Home Address, A Directory of All Churches, Public and Private Schools, Benevolent, Literary, Religious, and Other Societies, Banks and Trust Companies, A Compendium of the Federal Government, Officers of the State, County and City Governments, A Street and Avenue Guide, A Buyers Guide, and a Complete Classified Business Directory. Atlanta: Atlanta City Directory Company, 1919.

Bennett, David J. He Almost Changed the World: The Life and Times of Thomas Riley Marshall. Bloomington, Indiana: AuthorHouse, 2007.

Berg, A. Scott. Wilson. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 2013.

“Charles J. Haden Dies; Noted Georgia Historian,” Atlanta Journal, May 23, 1948.

“Charles J. Haden Dies; Southern Farm Leader,” Atlanta Constitution, May 23, 1948.

“False Report of Death Of the President Halts Address by Marshall,” Atlanta Constitution, November 24, 1919.

“He Generously Served Georgia and the South,” Atlanta Constitution, May 24, 1948.