The Great Locomotive Chase: Differing Perspectives

On June 18, 1862, seven men from Ohio were hanged just steps south of Oakland Cemetery. The leader of these men had been executed earlier, and several more waited in jail. In the Confederate states, these men were decried as spies, thieves, and “Lincolnites.” The people of the North would come to view them as heroes for their actions, and most of them have since been awarded the Medal of Honor.

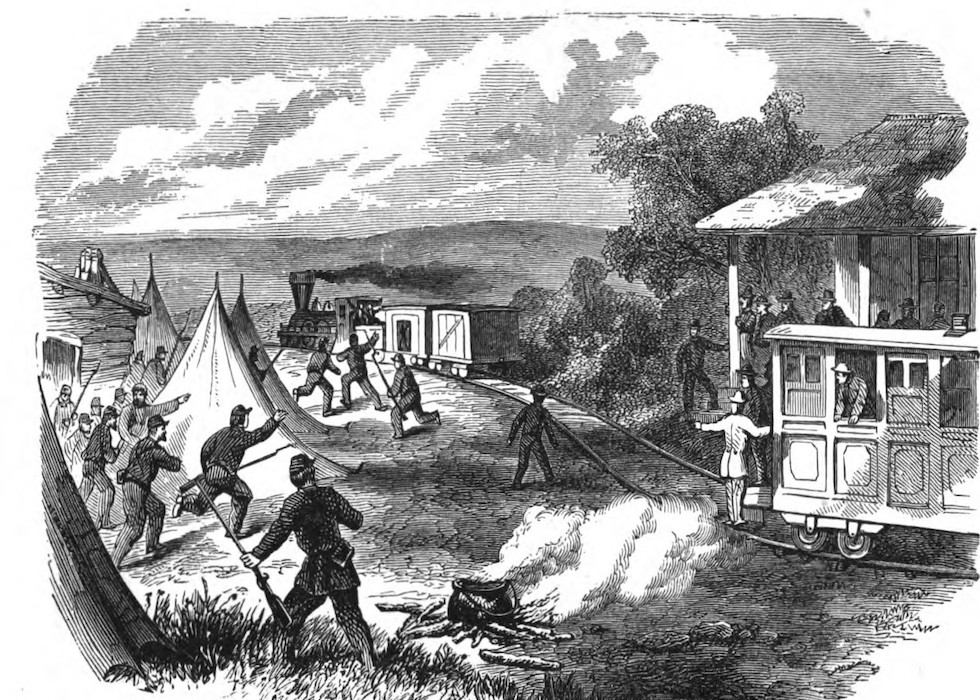

James J. Andrews, a civilian and Union spy from Kentucky, led this group of men in a daring raid to wound the Confederate states. In a small community north of Marietta called Big Shanty, known today as Kennesaw, Andrews and his “raiders” successfully captured the locomotive General on April 12, 1862. Andrews and his men planned to burn the railroad bridges on the strategically important Western & Atlantic Railroad but were ultimately unsuccessful. Andrews and his men were pursued by three railroad employees (and later Oakland residents), William Fuller, Jeff Cain, and Anthony Murphy. Fuller and his men pursued the General first on foot, then by rail pushcart, and finally on a series of three engines, the Yonah, William R. Smith, and finally the Texas. The General ran out of fuel north of Ringgold, and Andrews and his men were forced to flee into the Georgia wilderness. Had Andrews succeeded in his task, the Confederate supply lines running through Atlanta would have been substantially weakened, which could have brought about a swift end to the war.

Spies, Thieves, and “Lincolnites”

Various reports began circulating within days of what became known as the Andrews Raid. In Atlanta, the Commonwealth described the event as “either one of the most daring robberies or maddest pranks that has ever fallen under our notice.” The paper went on to chronicle the events of the chase and the capture of the Andrews Raiders.

“On Saturday morning eight of the party were arrested, and after being soundly whipped, confessed that they had been sent out from Shelbyville by the Federalists… this was certainly one of the most bold and reckless feats of the war, and had they succeeded in their designs would have been of incalculable injury to our cause.”

The Commonwealth also made it abundantly clear who the South found the heroes: the pursuers. The Andrews Raiders were referred to as “Lincoln’s Spies, Thieves, and Bridge-Burners” in the Augusta Chronicle. The article was a reprint from the Atlanta Intelligencer. All Southern articles give the same impression: the pursuers were heroes, and the raiders were villains. While the raiders were condemned, some did commend their cunning. The Southern Confederacy of Atlanta called it “the deepest laid scheme and on the grandest scale that ever emanated from the brains of any number of Yankees combined.”

Heroic Devotion

In the northern states, the sentiment was undoubtedly the opposite at this time, but this is not reflected in newspapers. The New York Tribune, the Philadelphia Inquirer, and the Fall River Evening News (of Massachusetts) all reprinted an article from the Richmond Dispatch, which itself was a reprint from the Atlanta Confederacy. The article the Northern papers choose to reprint refers to the raiders as “supposed… Lincolnites”. (7)(8)(9) No article written by Northerners, for Northerners has been found in newspapers so far from the months after the event.

The first articles with a pro-raider perspective were published in 1863 at the time of one of the most important parts of the Andrews Raid’s story. On March 25, 1863, raider Private Joseph Parrott received the very first Medal of Honor. Two days later, the Albany Evening Journal of New York described the raiders experience as a “dangerous expedition into Alabama,” and the men were praised for their “heroic devotion.” It also describes what they went through afterward, saying “one of them bears that marks of a hundred lashes inflicted upon him by the Rebels.”

The Cleveland Daily Ledger, quoting a now-lost copy of the Washington Chronicle, said the “rebel authorities treated [the raiders] with the greatest indignity and outrage.” The Cleveland Daily Ledger also described the hanging near Oakland Cemetery, saying the men “were executed with the expedition that people would execute a dog with hydrophobia… the inhuman agents of this infernal order were inexorable.” The Vermont Watchman and State Journal stated, “all of the survivors were treated with great brutality during their imprisonment.”

The Daily Morning Chronicle from Washington D.C. has one of the lengthiest articles from this time about the chase, which is largely a report of the Judge Advocate General to the Secretary of War. It said that the “expedition thus failed from causes which reflected neither upon the genius by which it was planned.” It elaborates on the importance of the event, as “the whole aspect of the war in the South and Southwest would have been at once changed.”

In 1863, William Pittenger, one of the raiders, published his account of the chase called “Daring and Suffering.” The book was popular and well-received by readers in the northern states and undoubtedly helped shape public opinion in the North about what had transpired. The book was reprinted in 1881 as “Capturing a Locomotive,” and in 1889 as “The Great Locomotive Chase,” giving the Andrews Raid its alternative title.

Film Perspectives

In 1926, Buster Keaton produced his silent comedy film, The General, based on the story of the Great Locomotive Chase. Keaton stars as the stolen train’s engineer, a loyal Confederate, who must chase down his engine’s thieves. The silent film star was inspired to create the movie after reading Pittenger’s account. Marion Meade, Keaton’s biographer, explained why he changed the hero from the Union to the Confederates, saying “the Yankees were the heroes and the Southerners the villains, which he feared movie audiences would not accept.”

A 2020 article by Kristin Hunt goes into much more detail about why Keaton chose to have a Southern hero. It credits the emerging prevalence of the “Lost Cause” theory, which had been promoted by Southern groups starting in the 1890s. Reviews for the film were just as divided as the original reports about the events the film was based on. Southern reviewers praised the Confederate heroism, but Northern papers felt the film was unfunny and lacked the seriousness required for a war film.

In Walt Disney’s 1956 film The Great Locomotive Chase, Andrews and his men are depicted as the film’s heroes. Like Keaton’s earlier film, the Disney movie was also inspired by Pittenger’s book though the film was drastically different than The General because of the differing protagonists. The New Georgia Encyclopedia also emphasizes the fact that Walt Disney’s The Great Locomotive Chase is based around “reconciliation between the North and South.” The NGE’s article elaborates further by saying “the film is ultimately not about a conflict between North and South but is rather an homage to the little man (or men) who fight the good fight against mass society. The film ultimately emphasizes the individual value of personal honor and bravery in wartime.”

In Walt Disney’s 1956 film The Great Locomotive Chase, Andrews and his men are depicted as the film’s heroes. Like Keaton’s earlier film, the Disney movie was also inspired by Pittenger’s book though the film was drastically different than The General because of the differing protagonists. The New Georgia Encyclopedia also emphasizes the fact that Walt Disney’s The Great Locomotive Chase is based around “reconciliation between the North and South.” The NGE’s article elaborates further by saying “the film is ultimately not about a conflict between North and South but is rather an homage to the little man (or men) who fight the good fight against mass society. The film ultimately emphasizes the individual value of personal honor and bravery in wartime.”

Today, the locomotive General can be found at the Southern Museum of Civil War and Locomotive History in Kennesaw. The Texas is housed at the Atlanta History Center, where the display emphasizes the importance of railroads to Atlanta instead of its role in the Great Locomotive Chase.

The story of the Great Locomotive Chase is exciting, but the story of public opinion about it is almost as fascinating. At the time of the event, it was viewed drastically differently in the North and South, with James J. Andrews and his men viewed as either noble heroes or dastardly villains. With the publishing and reprints of William Pittenger’s book, the nation at large was introduced to the opinion of the North, but by the 1920s it was felt only the Southern perspective would be well received by audiences. Finally, by the 1950s more emphasis was put on the spirit of reconciliation than the idea of Civil War heroes and villains. The story of the Great Locomotive Chase is not just a story of the theft of a train amid the Civil War, but the story of changing opinions about the conflict that divided our nation.

Andrew J. Bramlett is a 15-year-old historian living in Kennesaw, the site of the start of the Great Locomotive Chase. He was elected vice president of the Kennesaw Historical Society in 2015. He volunteers at Kennesaw Mountain National Battlefield Park, the Kennesaw Cemetery Preservation Commission, the Kennesaw Parks and Recreation Department, and the Friends of Kennesaw Mountain. In 2018, he won a Georgia Historical Records Advisory Council award for Local History Advocacy because of his work on presentations he gives about the history of the City of Kennesaw, Kennesaw Mountain, and his Kennesaw City Cemetery Walking Tour.

Andrew gives presentations, speaking to civic groups, senior centers, and community groups on a variety of topics ranging from local history to topics that can be used anywhere in the world. More info can be found on his website, ajbramlett.com.

Sources

April 4, 1862 Raleigh Dispatch

April 14, 1862 Augusta Chronicle

April 15, 1862 Augusta Chronicle

April 15, 1862 Southern Confederacy

April 23, 1862 New York Tribune

April 24, 1862 Philadelphia Enquirer

April 26, 1862 Fall River Evening News

March 27, 1863 Albany Evening Journal

April 4, 1863 Daily Morning Chronicle

March 31, 1863 Cleveland Daily Ledger

April 3, 1863 Vermont Watchman and State Journal

William Pittenger, “Daring and Suffering,” 1863