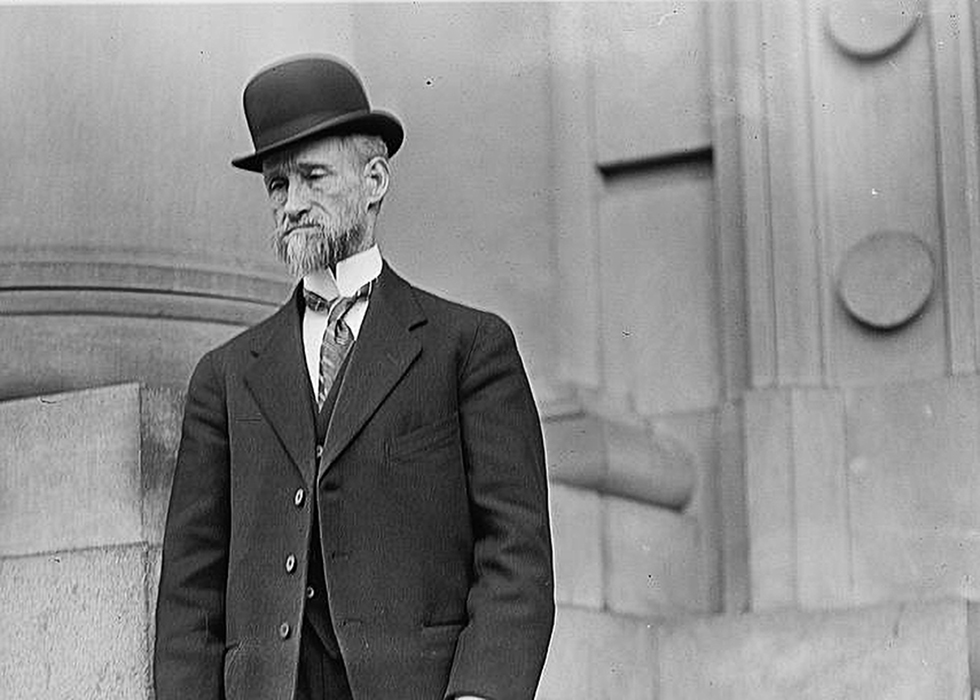

Resident Spotlight: Col. Henry Pattillo Farrow

Henry Patillo Farrow was born in Laurens, S.C., on Jan. 24, 1834 to lawyer Pattillo Farrow and Jane Strother James. He received his early education in Laurens and went to college at the University of Virginia, where he fought with his roommate and classmates on their differences of opinion on secession; Farrow was firmly against it. Upon returning Laurens Farrow studied law and engaged in pro-Union politics. He was admitted to the South Carolina bar in 1856.

In 1857 Farrow married Cornelia Finch Simpson. Unhappy with the political climate in South Carolina, he took his new bride to Cartersville, Ga., to practice law, make a home, and raise a family. In Georgia Farrow championed Stephen A. Douglas in 1860, serving as a delegate for him in the Democratic National Convention held in Charleston.

After Lincoln’s election Farrow continued to oppose secession, but he managed to avoid Confederate service for the first two years of the war. Eventually, he enlisted as an officer and was quickly placed in charge of the Department of Niter and Mining for the states of Georgia, Alabama, and Florida, a responsibility that carried the rank of Lt. Colonel. Farrow was responsible for providing the raw materials for the manufacture of munitions and powder, quite a challenging job late in the war (as will soon become evident.)

Although Farrow’s brothers and hometown friends were all of the secessionist persuasion, and his brothers became fine Confederate fighting leaders, he firmly believed that the country’s problems could be ironed out as long as it could hold together. He found like-minds in the Atlanta anti-secessionists, who formed a Union Association in 1860. Most of them were Northerners who had been in the south for decades and risen to positions of leadership in the community; Johnathon Norcross and William Markham were former mayors. Others were Needom Angier, a current city councilman, foundryman James Dunning, attorney Amherst Stone, and Alfred Austell, a banker and respected businessman. After the war, these men built the new Republican Party in the state and buffered, somewhat, the efforts of the Radicals, carpetbaggers, and political charlatans who flooded the post-war government. The men mentioned, except for Stone, all eventually came to lie in rest at Historic Oakland Cemetery, where their politics mattered no more.

“The ladies of Selma are respectfully requested to preserve the chamber lye collected about their premises for the purpose of making nitre. A barrel will be sent around daily to collect it.”

Farrow’s wartime experiences were more interesting than most. In the early years of the war, the Confederates had little trouble finding and harvesting necessary nitrates for the production of gunpowder. They could process the dirt of cave floors containing centuries of bat droppings, which yielded all the nitrates needed. However, as the war progressed and the Union army occupied most of the cave areas in Kentucky, Tennessee and northern Alabama, the Bureau of Nitre and Mining had to look to other places for it, mainly the dirt and manures of barnyards.

These soils could be soaked with urine and protected from rainwater dilution until saltpeter would form, producing the necessary nitre. Creating saltpeter to sell to the government led to a small, backyard business for farmers.

These “nitre beds” needed a constant soaking of urine to make them work, so one of Col. Farrow’s agents in Selma, Ala., John Harrelson, advertised the following in the local paper:

“The ladies of Selma are respectfully requested to preserve the chamber lye collected about their premises for the purpose of making nitre. A barrel will be sent around daily to collect it.”

As could be imagined, the public – especially the soldiers – had a great laugh over this, and from an unknown Southerner this poem came forth:

“An appeal to John Harrelson”

John Harrelson, John Harrelson, you are a wretched creature,

You’ve added to this war a new and awful feature,

You’d have us think while every man is bound to be a fighter,

The ladies, bless their pretty dears, should save their piss for nitre,

John Harrelson, John Harrelson, where did you get this notion,

To send your barrel around the town to gather up this lotion,

We thought the girls had work enough in making shirts and kissing,

But you have put the pretty dears to patriotic pissing,

John Harrelson, John Harrelson, do pray invent a neater

And somewhat less immodest mode of making your saltpeter,

For ‘tis an awful idea, John, gunpowdery and cranky,

That when a lady lifts her skirt, she’s killing off a Yankee.”

A little while later the Yankees got in on the fun with this retort:

“John Harrelson, John Harrelson, we’ve read in song and story

How a women’s tears through all the years have moistened fields of glory,

But never was it told before, how, ‘mid such scenes of slaughter,

Your Southern beauties dried their tears and went to making water,

No wonder that your boys are brave, who couldn’t be a fighter,

If every time he shot a gun he used his sweetheart’s nitre?

And, vice-versa, what could make a Yankee soldier sadder,

Than dodging bullets fired by a pretty woman’s bladder.”

Although he had served as a Confederate officer, during Reconstruction Farrow was considered sympathetic to the Republicans enough that the military commander appointed him to be the state attorney general under Governor Rufus Bullock. When President Grant was elected, he appointed Farrow to be the U.S. district attorney for Georgia, a position Farrow would hold for eight years. After that he was the collector of the Port of Brunswick, another federal job. After he focused his life on the North Georgia mountains, Farrow became the postmaster in Gainesville, while he and his wife ran the Queen of the Mountains Resort at the medicinal Porter Springs near Dahlonega.

Basil Porter owned the North Georgia property, but it was the Rev. Joseph McKee, a Dawson County Methodist minister who rediscovered the long-lost springs of Trahlyta, all filled-in with mud and trash, barely a trickle of flow. Rev. McKee cleaned out the springs, found stone containment walls from ancient times, and people started coming to treat their ailments with the wonderful water.

Henry Farrow came to Porter Springs to treat a war injury that had never healed, and the waters did their magic. So taken with the success of the treatments, Farrow bought the land from Porter, and developed it into a hotel, cabins, ballroom, dining room, tennis courts, croquet fields, and billiard parlor. As others experienced healing from chronic conditions, the word spread, and the facility was flooded with success. Boarding rates at the Queen of the Mountains Resort were $1.50 per day or $22.50 a month, including delicious meals accompanied by orchestra music. The business prospered, furnishing the Farrows with purpose until old age took them away. Cornelia passed at the resort on August 16, 1904, and Henry at his daughter’s house on Pryor Street in Atlanta, three years later on February 10, 1907.

Today the family sleeps across the street from the Austells, beneath the sweet soil of Historic Oakland Cemetery.