Governors of Oakland: Joseph E. Brown

Oakland Cemetery is home to many important mayors, celebrities, and public officials. Among these individuals are six governors who today reside inside its hallowed grounds. This blog series will explore these six men: their successes, their failures, and their impact on the people of Georgia.

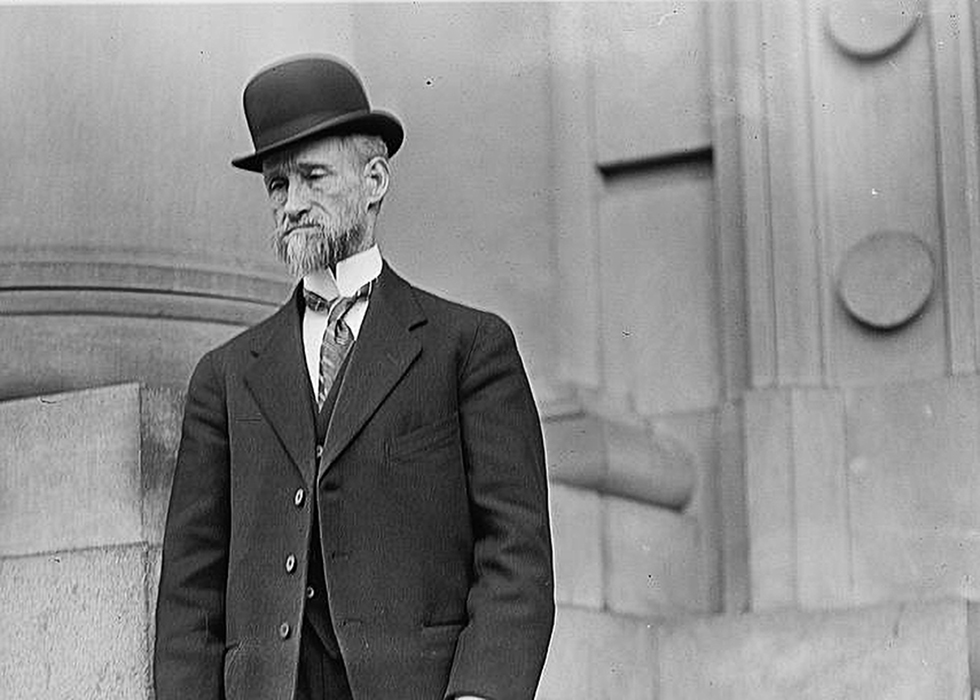

The best-known quote about Joseph Emerson Brown comes from Robert Toombs, a Civil War-era politician in Georgia: “Who the devil is Joe Brown?” Born in South Carolina in 1821, Joseph Emerson Brown and his family moved to Georgia when he was eight. Brown attended law school in South Carolina and Georgia, passing the bar in 1845. He became a minor figure in the Georgia Democratic Party. During the 1857 gubernatorial election, Brown was nominated as a dark-horse candidate. This prompted Toombs’ query. Brown emerged from the contest victorious and would go on to serve four terms as governor of Georgia. Many liken him to Andrew Jackson. Like Jackson, Brown was a man of the people. He was perfectly willing to use the veto. Similar to Jackson’s attacks on the Bank of the United States, Brown was viewed as an enemy to bankers.

The best-known quote about Joseph Emerson Brown comes from Robert Toombs, a Civil War-era politician in Georgia: “Who the devil is Joe Brown?” Born in South Carolina in 1821, Joseph Emerson Brown and his family moved to Georgia when he was eight. Brown attended law school in South Carolina and Georgia, passing the bar in 1845. He became a minor figure in the Georgia Democratic Party. During the 1857 gubernatorial election, Brown was nominated as a dark-horse candidate. This prompted Toombs’ query. Brown emerged from the contest victorious and would go on to serve four terms as governor of Georgia. Many liken him to Andrew Jackson. Like Jackson, Brown was a man of the people. He was perfectly willing to use the veto. Similar to Jackson’s attacks on the Bank of the United States, Brown was viewed as an enemy to bankers.

By the time Brown entered office, the writing was on the wall about a conflict between the northern and south states. In his first two terms, Brown worked to prepare Georgia for war. Brown was an ardent advocate for slavery. As historian Thomas Robson Hay noted in 1929, Brown believed both slaveholders and non-slaveholders derived benefits from the system of racial inequality perpetuated by slavery. Brown also made it clear that he would lead Georgia to secede from the Union to prevent the abolition of slavery, which he predicted would be the “utter ruin of the South.”

Brown was initially more than willing to serve the Confederacy, but he gradually became antagonistic to Confederate President Jefferson Davis. Brown referred to Davis as a “dictator.” The two men mainly disagreed over military matters, though Brown also felt the Confederacy challenged state autonomy. He disapproved that the Confederate government oversaw military recruitment operations. Brown felt state governors should have more power in choosing military officers. Rumors had begun to spread of Brown’s discontent only one month after the war began. While Brown openly disliked Jefferson Davis, he did find an ally in Alexander H. Stephens, vice president of the Confederacy.

Imprisoned at the end of the war, Brown was pardoned and then resigned as governor. Brown switched to the Republican Party. In 1868, he was appointed to serve as chief justice of the Georgia Supreme Court, a position he held until 1870. In 1880, Brown switched his allegiance back to the Democratic party when he was appointed to the U.S. Senate. Brown and two other men, Alfred H. Colquitt and John Brown Gordon, dominated Georgia politics in the years following Reconstruction. Together, the three politicians were known as “The Bourbon Triumvirate.” The term referred to the toppled conservative monarchs of France. The three men supported the idea of a “New South,” a movement that called on southern states to industrialize while reinforcing white supremacy in its institutions. Brown served in the Senate until 1891.

Brown became a successful business leader, and much of that money came from leased prisoners under the convict lease system. Early in its history, the convict lease system used both white and Black prisoners, but it would later be known for disproportionately affecting African Americans. The system is often compared to slavery, or referred to as “slavery by another name.”

Joseph E. Brown has been called an opportunist, an obstructionist, a Confederate patriot, a powerful business leader, and an Andrew Jackson-like figure. His complex legacy includes his support of slavery, his work to reconcile Georgia into the Union, his efforts to industrialize the “Empire State of the South,” and his promotion of the convict lease program. When he died in 1894, Joseph Emerson Brown was considered one of the wealthiest and most powerful men in Georgia.

Joseph Emerson Brown came to rest in Oakland Cemetery following his death. He is buried near his wife Elizabeth, who he married in 1847. The couple shares a statue on the grounds of the state capitol. Their son, Joseph M. Brown, later served as governor of Georgia and rests nearby.

Joseph Emerson Brown came to rest in Oakland Cemetery following his death. He is buried near his wife Elizabeth, who he married in 1847. The couple shares a statue on the grounds of the state capitol. Their son, Joseph M. Brown, later served as governor of Georgia and rests nearby.

Andrew J. Bramlett is a 15-year-old historian living in Kennesaw, the site of the start of the Great Locomotive Chase. He was elected vice president of the Kennesaw Historical Society in 2015. He volunteers at Kennesaw Mountain National Battlefield Park, the Kennesaw Cemetery Preservation Commission, the Kennesaw Parks and Recreation Department, and the Friends of Kennesaw Mountain. In 2018, he won a Georgia Historical Records Advisory Council award for Local History Advocacy because of his work on presentations he gives about the history of the City of Kennesaw, Kennesaw Mountain, and his Kennesaw City Cemetery Walking Tour.

Andrew gives presentations, speaking to civic groups, senior centers, and community groups on a variety of topics ranging from local history to topics that can be used anywhere in the world. More info can be found on his website, ajbramlett.com.