Oakland Cemetery’s Early Landscapes: The Fence and the Wall

Very old photographs of familiar places are most intriguing to many people, particularly those with an interest in history. Oakland Cemetery is no exception; old photographs illustrate how Oakland grew, how it changed with decades of improvements, and in some cases what has been lost to the vagaries of time. These early images are quite intriguing as to the landscape and gardening at Oakland, helping to inform staff on appropriate plant selections and landscape motifs with restoration projects.

But photographs only go so far, providing disparate visual mileposts to anchor the understanding of Oakland’s changing landscape.

One of Oakland’s most dominant features is its enclosure. The brick and granite perimeter wall sets Oakland apart from its immediate surroundings, and with the passage of time now signals the venerable age of the landscape within. However, in the beginning, the cemetery’s perimeter enclosure was all about providing basic security (and at a cost the City could afford.) For the first 40 years, numerous wood fences protected the cemetery. In a Southern climate, this proved both short-lived and a regular drain on the City’s budget.

Soon after the City purchased the Original Six Acres for the “City Grave Yard” in 1850, expenditures were requested for building a fence. In March 1851, it was “Resolved that the grave yard be enclosed with post and plank fence, panels to be eight feet in length.” However, it seems the fence wasn’t actually constructed until 1855, based on a terse line in the Annual Report made to the Atlanta City Council for the year: “A contract has been made with D. Demorest, Esq., for the building of a substantial fence around the Yard for the sum of $225.”

For the first 40 years, numerous wood fences protected the cemetery. In a Southern climate, this proved both short-lived and a regular drain on the City’s budget.

It only took three years for the fence to decay and require another infusion of funds. In June of 1858, the City Council’s Committee on Cemetery reported, “that after having taken down the old fence on eastern end of the Cemetery they found that about one half of the material is so rotton [sic] that it is unfit for use, and will have to be replaced by new material.”

No surprise, the Civil War took its toll on the fence as it did on the rest of Atlanta. Letters and military reports lament the Federals’ burning of the fence and palings around graves; lesser offenses like grazing their horses; and acts of vandalism and desecration. The Chairman of the Committee on Cemetery pressed for a new fence as early as practicable, to be constructed “with sound oak posts with base or bottom board 12 inches wide and [four] 6-inch boards above also an upright or joint board to each post. Can be put up for $700.” In 1869 a mention is made that the front gate needed a post (perhaps because of rot) but no mention is made alluding to the gate’s appearance.

The early 1870s mark the evolution of Oakland from a small-town graveyard to the municipal cemetery of a rural landscape design we know today. As the newly acquired land was laid out, surveyed and developed, a new fence was in order to replace the dilapidated old one and enclose the new land. Bids were advertised in the local newspapers in June 1871, and in July J.D. Wofford’s bid was accepted at $8.43 per panel. Wofford’s fence was completed in September.

Interestingly, Wofford’s fence doesn’t seem to have run along the side adjacent to the Georgia Railroad tracks. The following spring of 1872, a new fence was requested to be in the same design as Wofford’s, using the sound timber from the old fence “in strengthening the two ends.” This same year, the City opened up Hunter Street (now Martin Luther King Jr. Drive), finally constructing a direct street from the main part of town to the cemetery, thus bypassing the old circuitous route families used to visit the cemetery. In response to the new road, new arched gateways were built at the main Hunter Street and secondary Fair Street entrances. And to christen the new look of the transforming cemetery, it was finally bequeathed a name, “Oakland.” On March 22, 1873, the Atlanta Daily Sun reported that a resolution was adopted “to have the proper name of [the] City Cemetery put on each entrance.”

Thus, the general configuration of the fence for the next 25 years is set – two primary gates on the perimeter roads (Hunter Street and Fair Street, now Memorial Drive) and a small third gate for north pedestrian and railroad access. The arched “Oakland Cemetery” gates likely were incorporated into early stylized engravings of Oakland and the Confederate Grounds. Two well-known images, one from Illustrated History of Atlanta (1877) and one from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Weekly (1881), show a simple solid arch set on square pillars. While not completely accurate, the engravings do provide a sense of how Oakland now greeted its visitors.

Six years pass and the wood fence is again in need of repair, and the City earmarked $75 for the job in 1878. However, the fence was still badly decayed in 1880, and by 1882 the repair costs were estimated at $600. The City Council and Board of Aldermen did agree in 1882 to move the north gate to a more accessible convenience location, as the appropriation was only $5. However, the Aldermen declined a request to install a small, convenient pedestrian gate on the south fence, deeming it as unnecessary despite its $5 price tag.

Mayor Hillyer remarked upon the fence’s sorry state of affairs in his 1885 New Year’s address, acknowledging the cemetery needed a new fence.

The new fence didn’t happen until 1887, but by then it came with a 300-foot rock wall, the impetus for the brick wall we know today. This first rock wall started at the southwest corner of the cemetery (now the corner of Memorial Drive and Oakland Avenue) and extended along Fair Street to the east. The repaired fence was then repainted, so far the only indication that the fence was not just raw wood.

This version of the fence is clearly rendered in the 1892 bird’s eye view of Atlanta, a map of which hangs in the Bell Tower gift shop. The main Hunter Street gate is double-arched, seemingly the more elaborate of the two. The second arched gate on Fair Street is less grand, and a third simple gate is directly behind the Bell Tower. This was reportedly known as Cemetery Crossing. Glimpses of the fence can be caught in the background of a circa 1895 stereoview, looking north near the Governor Brown monument.

A quick inspection of the bird’s eye view map reveals no fence nor wall, but open grass and a meandering creek along the east side of the cemetery. The now-iconic granite rock wall, along what was then called South Boulevard street, was constructed in 1892. Financed by the sale of around 70 vacant lots owned by the City, it rendered “that portion of the cemetery more safe and presentable.” Council minutes indicate the ordinance for the project was passed in July 1892, suggesting the map was made prior to the start of construction, and so provides documentation as to Oakland’s changing landscape over its development.

Finally, after decades of fence repairs, the City agreed to and paid for a brick wall. Originally, a rock wall was requested by the Committee on Cemetery in 1894, but it seems brick was deemed more prudent. Proud of the results, the Chairman for the Committee on Cemetery reported in 1896 the cemetery “is now nearly enclosed by a neat and permanent wall, capped with an iron fence. There only remains about 400 feet to be built on the north side, along the Georgia railroad, where a retaining wall is necessary.” The Hunter Street (main) gate was built at the same time for $1,200; Bruce & Morgan Architects designed the gate, while the local firms of Venable & Collins Granite Company (office on Broad Street) provided stonework and Gate City Fence Works on Edgewood Avenue provided the wrought iron fencing. The Hunter Street gate bears a striking resemblance to George Washington’s tomb, constructed in 1831 and doubtless the inspiration for many cemetery gates across the country.

Construction of the brick wall brought a number of changes regarding the secondary gates. The third gate in the wood fence, located directly behind the Sexton’s Office providing access to the train tracks, was moved west to the lowest spot. This made the gate “on-grade” to the railroad track bed, obviating the need for steps down to the tracks, and allowed for a drainage system. Happily, the small pedestrian gate deemed unnecessary in 1882 was finally constructed, located at what is now Jewish Hill, halfway between Boulevard and the Fair Street gate. This is almost at the corner of Park Drive, where the old trolleys once turned south to head down to Grant Park. A new, small pedestrian gate was constructed at the northwest corner of the cemetery, close to the MARTA station and designed to provide visitor access for those coming from the north at Young Street across Decatur Street and the railroad tracks. The terracotta tile coping was installed atop the wall for protection in 1909.

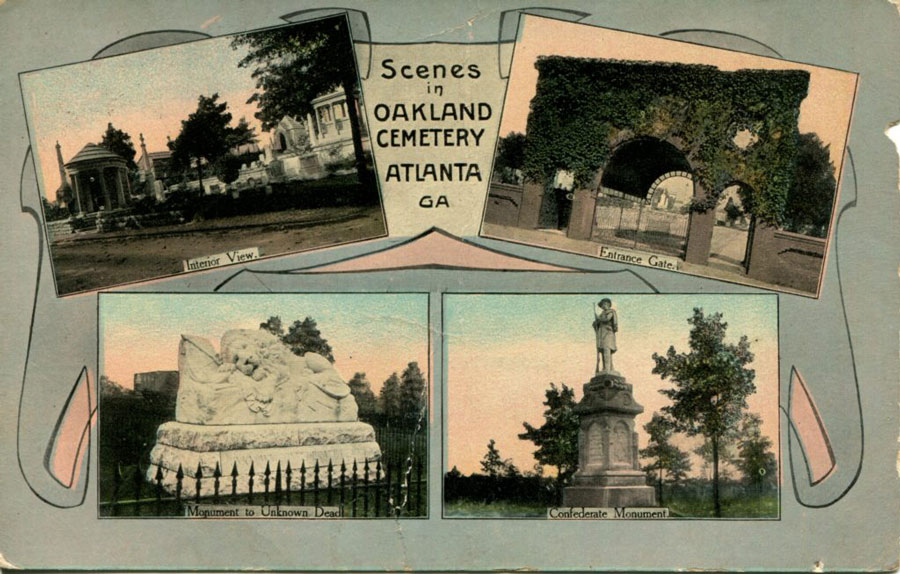

It is not clear when the large Fair Street gate was built, but presumably, it was built along with the Hunter Street gate when the brick wall was built in 1896. Its design motif was also popular across the country at the time. A galvanized iron canopy was added in 1910 at a cost of $440, providing shelter for visitors presumably as they waited for the trolley. Most of the gate’s early images show it covered in ivy, a popular romantic motif in the Victorian and Edwardian eras. One rare image of the gate, dating from the middle 20th century, shows the gate fully exposed.

The Hunter Street gate was re-built in 1966 with assistance from the National Park Service as part of their Mission 66 program. Celebrating 50 years of the National Park Service, Mission 66 was tasked with identifying and preserving America’s heritage. For reasons unknown, the gate was not completely rebuilt to its original appearance; two decorative Corinthian inset pieces towards the top of the two main columns were not kept and were instead replaced with plain brick. It is suspected that the Fair Street gate was disassembled at this time, taken down to the basic columns of today.

The brick wall was restored in 1998 following the original design, but with reinforcing systems, and re-used 30% of the original brick. Barring unforeseen accidents, Oakland’s walls should stand for another 100 years.