Digging Deeper: Labor in the 19th-Century Cemetery

This blog post was written by Ashley Shares, HOF director of preservation and Liz Clappin, host of the weekly podcast, “Tomb with a View.”

The last time you took a tour of a cemetery, did you learn about the famous residents, their lives, accomplishments, and deaths? Did the tour guide point out quirky epitaphs, poignant symbols, and unique mausoleums? We imagine the answer must be “yes—on all counts!” But how many of you have ever stopped to ponder how that cemetery came to look as it does or who was responsible? See, all too often cemetery lovers forget the most important story of all: The story of the people behind it all: those who erected the monuments, buildings, and walls; planted the trees; laid the walkways; and dug the graves. Without their stories, there would be no others to tell. Today, we’re digging deeper. We’ll focus on cemetery laborers in Atlanta’s Oakland Cemetery, and consider how the experience of workers at Oakland was different from those working in northern cities like Philadelphia.

Prior to the 19th century, most small cemeteries, whether public or private, had some form of caretaker, often a gravedigger who also helped keep the cemetery tidy. As cemeteries and the cities they served grew, demands for their services increased and this role became more complex. The earliest records we have indicate that Oakland was maintained by a sexton and possibly three other laborers. In 1869, the sexton’s salary was fixed at $1000 per year, where it remained for nearly two decades. Prior to this, the Sexton received a sort of “commission,” a portion of the fee charged for each burial he supervised.

Based on Atlanta City Council records, the biggest challenge faced by sextons seems to have been record-keeping and mapping the plots in the cemetery.

The sexton was responsible for lot selection and sales, for ensuring that graves were opened in a timely manner, for filing legal paperwork, and for ensuring that records were kept. Most importantly, the sexton served in a managerial role, making sure that there was sufficient staff to carry out the necessary duties of maintaining the cemetery, including day-to-day groundskeeping and maintenance. Based on Atlanta City Council records, the biggest challenge faced by sextons seems to have been record-keeping and mapping the plots in the cemetery. The consistent underperformance of the sextons in this capacity spurred the Council to bring in outside surveyors on multiple occasions to assist. Despite their lack of map-making and record-keeping skills, the sextons who labored at Oakland were praised by the public and City Council for their ability to upkeep the grounds:

“The grounds, owing to the efficiency and energy deployed by our competent and obliging Sexton, are under a high state of cultivation, and are daily undergoing a rapid improvement, and while it is a melancholy duty to visit such a spot we must say that our sorrows are greatly mitigated to see that the bones of our dead are so tenderly and neatly cared for as they are in our own Cemetery.” (Annual) Report of Committee on Cemetery, Atlanta Ga., Dec. 31 1872.

As cemeteries like Oakland grew and diversified, the need for a skilled workforce grew with them. The original six-acre city cemetery expanded to its current size of 48 acres in just 16 years. The new land needed to be cleared, graded, and platted for burials. At the same time, the cemetery took on more characteristics of the rural cemetery movement, which promoted burial grounds as picturesque landscapes. As a result, the pathways and fencing needed constant upkeep, as did the plantings and grass. In the second half of the 19th-century buildings were erected on the cemetery grounds, many by the skilled artisans on staff at the cemetery. Maintenance of the cemetery now required not just gardeners and gravediggers, but also experienced artisans familiar with trades like stone and brick masonry.

The work was consistent, paid well, and offered the opportunity to work outside in a healthier climate than what many factory workers faced.

Both sextons and laborers at Oakland usually came from a working-class or skilled-labor background. Some of the earliest sextons were carpenters, brick masons, operators of livery stables, police officers, and gardeners. Laborers and grave diggers were often either rural farmers who migrated to the city or workers previously employed in other skilled trades. Security guards came from police or military backgrounds; if they were employed in the 1870s and 1880s, many were veterans of the Civil War. With a few exceptions, almost all laborers, guards, and sextons at Oakland were native-born, a sharp contrast to other East Coast cities where the majority of cemetery workers were recent immigrants. In Philadelphia, the largest body of cemetery workers appears to have been Irish and German immigrants who immigrated in the mid-19th century. Cemetery jobs, in both the North and South, offered similar opportunities to those newly arrived in cities. The work was consistent, paid well, and offered the opportunity to work outside in a healthier climate than what many factory workers faced.

Because of their working-class status, laborers commuted to work on foot, meaning that in the 19th century, all of the cemetery workers we looked at either lived in the cemetery where they were employed or within one mile of it. They were almost exclusively renters and moved frequently. In 1890, only about a quarter of Atlantans owned their own homes. Although at one time the City of Atlanta did provide living arrangements for the sexton and his family, as far as we know, no one has ever lived at Oakland Cemetery. Although Oakland may not have had staff living on-site, workers’ pay may have been higher, since room and board were considered part of many sextons’ salaries. This was not the case for many private cemeteries in northern cities like Philadelphia. Laurel Hill Cemetery, the most famous of the rural cemeteries of Philadelphia, had different families living at each of its three gates.

We’ve barely scratched the surface of the story of 19th-century cemetery labor, and although Liz and Ashley could write on and on regarding the subject, we think you’ll like hearing their voices instead. Please listen to episode 68 of TOMB WITH A VIEW (Spotify / Apple Podcasts). We’ll go into greater detail and give you a clear picture of what life and work were like for those whose efforts 150 years ago are the reason there are cemeteries worth visiting.

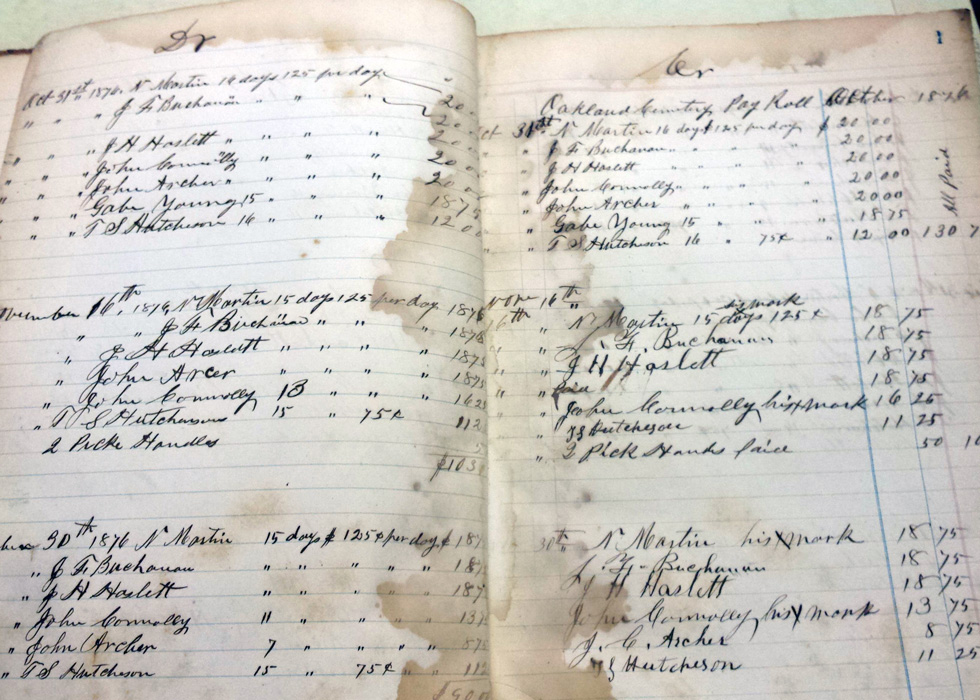

Feature photo: Oakland Cemetery payroll book, Atlanta History Center archives.

Keep Reading

Wait, you work at a cemetery? What it’s Like to Intern at Oakland

"Wait, you work at a cemetery?" For the past year and a…

Preservation Made Easier via Heavy Equipment and Outside Support

Visitors to Oakland Cemetery are often surprised to learn the scale of…

Resident Spotlight: Green Pilgrim, Oakland’s Second Sexton

Last week the PRO Team tackled some long-overdue critical projects across the…